The policy world has a strange way of misallocating attention. Major, systemic problems languish in obscurity for years; relatively minor issues attract armies of experts and millions in funding. As an economist friend once told me, there’s no efficient market for wonkery.

This mismatch creates opportunity. There are whole areas of research out there just waiting for their champion. I’ve encountered a few in my work—and unfortunately, I don’t have the bandwidth to pursue all of them myself. So, in the hope that it spurs someone to take them on, I’m sharing three ideas here.

Idea 1: What Happened to the Davies List?

Back in 2001, Terry Davies and Resources for the Future dropped what is still the best permitting paper ever written. For the uninitiated, Davies is a legend of environmental policy—he wrote the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), more or less co-founded the EPA, and was influential in the design of the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act.

The aptly-named “Reforming Permitting” spans 104 pages and probably has my favorite opening line ever…

But I digress.

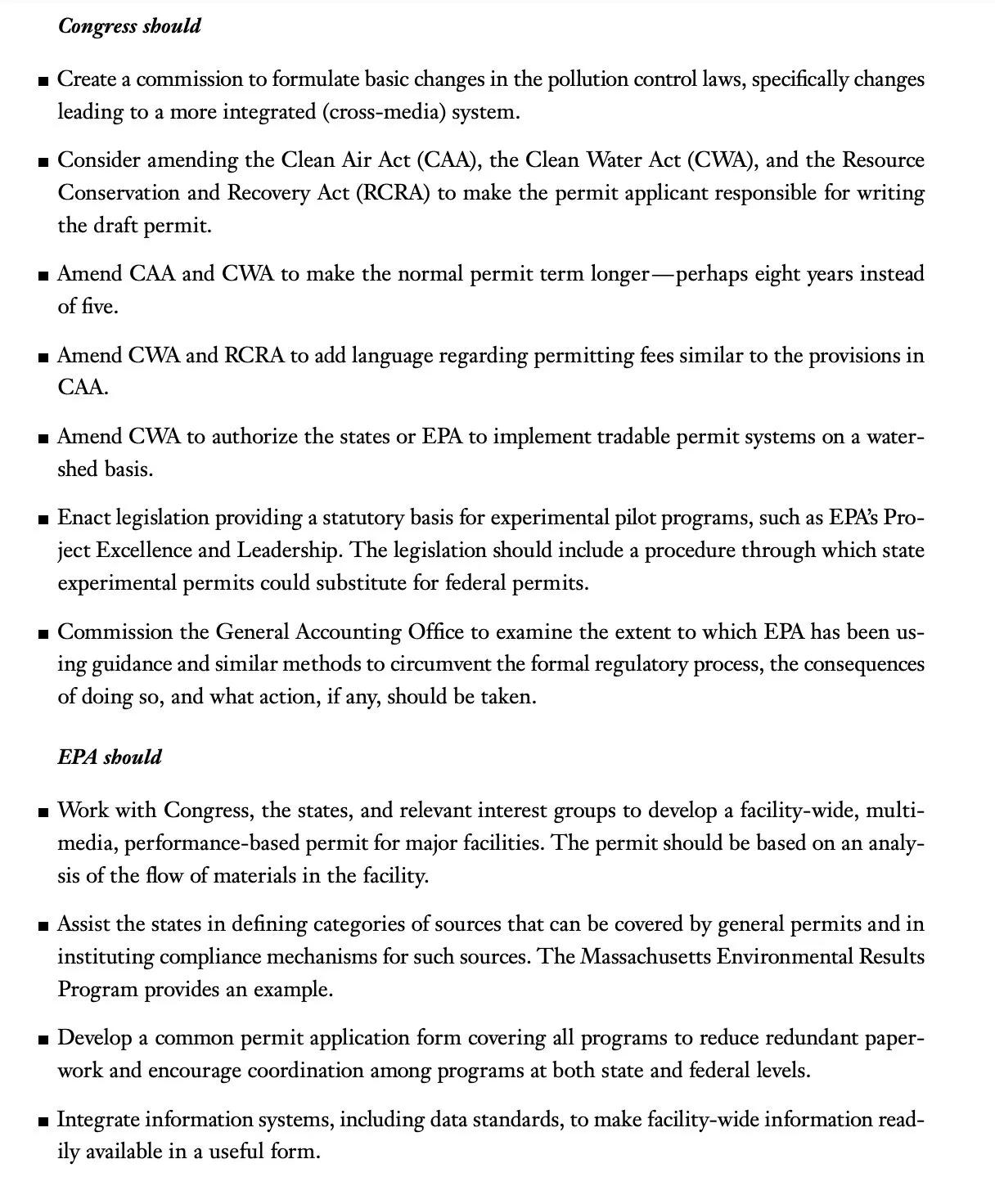

The most relevant part is this: the Executive Summary has two pages of recommendations for Congress, EPA, states, industry, and environmental groups.

A few things here:

First, 24 years later, approximately zero of these recommendations have been adopted. Almost all of these ideas are still relevant, too, from the Clean Air Act’s permit terms to multi-media permitting. So I think it would be fascinating to know where the disconnect was—after all, RFF was quite an influential think tank around the turn of the millennium, and Davies in particular had worked in EPA, CEQ, and “virtually [every] committee or group that has tried to look comprehensively at the base of our environmental law.” Did permitting reform just not feel urgent in Congress in 2001? Did the mess of Project XL and the Common Sense Initiative poison the well? I’d love to know.

Second, we seem to have forgotten about these ideas. Nobody in the current permitting reform discussion seems to be talking about experimental pilot programs or tradable permit systems. Why is that? I have a guess or two—for example, the new generation of permitting reform advocacy has largely emerged out of a desire to fight climate change, which has shifted attention away from pollution control laws and towards procedural laws like NEPA, the Endangered Species Act, and the National Historic Preservation Act. But still, it’s fascinating and befuddling that there seems to be no continuity or development in ideas from the last “golden age” of permitting reform (late 90s-early 2000s) to the current one.

Finally, Davies lays out his ideas in brief in the executive summary—but each one of them could be built out on their own in a research paper. This, in particular, seems ripe for the picking.